The Weight of Conformity: Loneliness in Collectivist Culture

Balancing individuality and collective harmony in a paradox of connection and isolation

When I first arrived in Đà Nẵng, Vietnam, for a month-long creative residency, it didn’t take long to notice the way people were deeply intertwined in each other’s lives. Multiple generations—children, parents, and grandparents—gathered together in daily rhythms. Neighbors shared food and drinks, and karaoke machines—impressive ones, I might add—filled the air with song as communities celebrated in preparation for Tết, the Vietnamese New Year. For someone with a predominantly Eurocentric worldview, accustomed to hyper-individualized structures and a lack of community-driven public spaces, this way of life felt refreshing.

On the surface, it seemed as though loneliness and even aloneness might be rarer here.

But beneath the surface, the story is more complex.

Compared to my observations in southern China last year, where similar communal patterns exist, Vietnam feels less affected by technological detachment. In China, mobile-first interactions dominate daily life, creating an eerie disconnection as people stare at their phones instead of engaging face-to-face. Both nations share key dynamics as collectivist cultures, deeply rooted in traditions of group harmony and group cohesion. These cultural frameworks coexist with decades of political systems marked by repressive policies and limited freedoms.

Unlike many democratic, liberal cultures in the West, where personal needs are put first, these societies prioritize the collective good.

But how does loneliness manifest in a culture where the individual self is subordinate to the collective?

Can loneliness exist when you are never physically alone?

Or is it precisely the negation of the self that deepens feelings of isolation—even within the “we” of a collective?

Conformity as a Cultural Norm

Research by Luiza Heu and colleagues at the University of Groningen reveals that loneliness is a qualitatively similar experience across cultures. Interestingly, their findings suggest that loneliness can be even higher in collectivist cultures than in individualist ones. The reason? Social norms. These unspoken rules dictate “how one ought to behave” to fit in, often at the cost of authenticity.

As Brené Brown has noted, “fitting in is the opposite of belonging.”

In collectivist cultures, these norms may be particularly rigid, placing immense pressure on individuals to conform, often stifling their authentic selves and deepening feelings of disconnection.

Hong Tang, founder and CEO of Catalyst For Change Vietnam, whom I connected with here, offers a firsthand perspective.

Her journey began far from the bustling cities of Vietnam. Growing up in a rural village, she learned English by listening to tourists and picking up the skills quickly, eventually leading to opportunities in tourism and hospitality in Hanoi. However, her life took a sharp turn when she became a single mother at 26—a status still heavily stigmatized in Vietnam. Struggling with societal judgment and isolation, Tang turned to writing a blog and created an online community where women could share their experiences anonymously.

This virtual network became the foundation for Catalyst For Change Vietnam, a nonprofit organization dedicated to empowering single mothers, women, and other marginalized groups. Today, the organization provides not only mental health support and financial aid but also fosters social connections through safe spaces where vulnerability is embraced rather than shamed.

Tang shares:

“In a country like Vietnam, where there is no philosophical or cultural framework for individual reasoning, anyone who thinks a little deeper than the general requirement can fall into loneliness quickly. It’s easy to feel disconnected when questioning societal norms.”

For example, societal expectations often dictate relationships.

“Having a large network or a perfect family is a mark of being a good person,” she explains. “It’s less about meaningful connections and more about fulfilling societal ideals. At Tết, year-end parties, or family meals, there’s a cultural obligation to show up, no matter how you feel. This pressure to conform means young people often eat quickly at family gatherings just to escape prolonged scrutiny.”

The Absence of Emotional Language

In Vietnam, the concept of emotional expression can be limited.

“People here don’t talk about feeling hungry, upset, or annoyed. Sharing struggles is seen as weak. It’s a legacy from our history of war, where resilience and strength, both physical and mental, were essential for survival. Even now, people don’t know how to recognize or express their feelings.”

This stigma extends even to safe spaces. Tang’s organization hosts a community for single mothers, yet many women post anonymously. “Even among people in the same situation, they fear judgment. They share, but they prefer to hide who they are.”

The stigma around loneliness is closely tied to shame. Hong’s mother, for instance, frequently says she feels lonely, even while living with family.

“Her loneliness comes from feeling misunderstood,” Hong explains. “But instead of expressing it, she pressures my brother to build a big house, believing this will restore her social standing. It’s about meeting societal expectations rather than addressing real emotional needs.”

Generational Shifts Across East Asia

Vietnam isn’t alone in grappling with the interplay of collectivist norms and loneliness. In South Korea, young people are categorized into generational archetypes like “the three-giving-up generation”, referring to those who abandon relationships, marriage, and children due to societal and economic pressures. The phenomenon extends to “five-giving-up” and even “total-giving-up” generations, where hope itself is relinquished. Terms like “honjok” (“lonely tribe”) describe the increasing isolation of youth.

Japan’s hikikomori population—individuals who withdraw entirely from society—has gained global attention and finds parallels in Western contexts, in what Derek Thompson described as “the anti-social century.”

Similarly, in China, mental health conversations are emerging on platforms like Xiaohongshu, but stigma persists, especially among family and peers. An emerging trend among young Chinese consumers is what’s known as “lazy health”. This approach emphasizes low-effort methods for maintaining well-being, such as foot soaking, early bedtimes, and consuming health supplements like herbal teas and vitamins. Practices like temple visits and micro-short drama viewing provide quick escapes from daily stresses.

Local markets have also become social hubs, offering healing through nostalgia and sensory engagement. Despite these efforts, loneliness and isolation remain significant challenges for urban youth, who turn to social media for connection and advice. The rise of "punk health" reflects an attempt to balance self-care with occasional indulgence, integrating wellness into fast-paced lifestyles.

While the specific drivers of loneliness may differ across cultures, the experience itself is a universal aspect of the human experience.

In collectivist societies, the tension between societal expectations and individual desires can create a unique form of loneliness—where individuals feel isolated, despite being surrounded by others.

In Western societies, the emphasis on individuality can lead to hyper-independence (“I don’t need anyone”). In contrast, collectivist cultures risk erasing individuality altogether. So, how do we strike a balance? How can we honor the self while maintaining the interdependence that is essential for collective well-being?

True connection may lie in reframing social norms—slowly, intentionally—to create spaces where both the self and the collective can coexist. As societies grapple with globalization, rapid urbanization, and technological transformation, there’s much to learn from both the strengths and vulnerabilities of collectivist and individualist paradigms.

As Hong Tang reflects: “Loneliness isn’t about whether you live in a collectivist or individualist society. It’s about whether you feel truly seen—by others and by yourself.”

Thank you for reading! As always, feel free to share your experiences, and observations, and comment how this piece resonated with you.💛

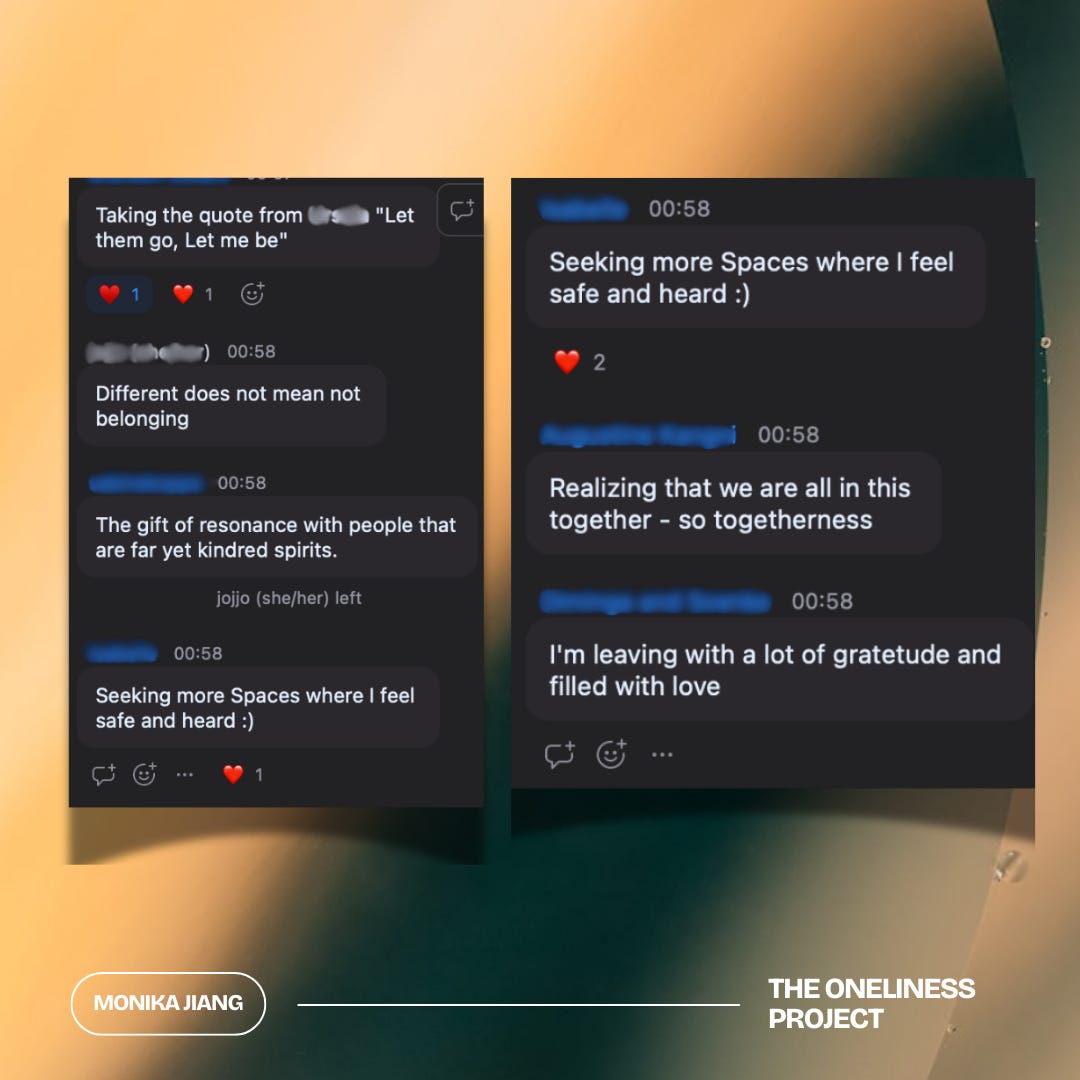

The Oneliness Project is rooted in the belief that loneliness is both a personal and societal experience, we explore what it means to foster care, build meaningful relationships, and nurture a sense of interconnectedness—oneliness.

Join the community to exchange and share with others, take part in our monthly Oneliness Circles or upcoming learning programs, or inquire about custom talks and workshops or 1:1 mentoring.

Plus: leave a note as part of 🎙️ The Oneliness Voices, a new collective audio storytelling project to humanize loneliness through the power of stories!